What Is The Main Factor In Determining Domestication Of A Plant Or Animal Quizlet

Dogs and sheep were amongst the first animals to exist domesticated.

Domestication is a sustained multi-generational relationship in which humans assume a meaning degree of command over the reproduction and care of some other grouping of organisms to secure a more than predictable supply of resources from that group.[1] The domestication of plants and animals was a major cultural innovation ranked in importance with the conquest of fire, the manufacturing of tools, and the evolution of exact language.[2]

Charles Darwin recognized the minor number of traits that made domestic species different from their wild ancestors. He was also the start to recognize the difference between witting selective breeding in which humans directly select for desirable traits, and unconscious pick where traits evolve every bit a by-product of natural pick or from selection on other traits.[3] [4] [v] There is a genetic divergence between domestic and wild populations. There is besides such a difference betwixt the domestication traits that researchers believe to take been essential at the early on stages of domestication, and the improvement traits that have appeared since the separate between wild and domestic populations.[vi] [7] [8] Domestication traits are generally fixed within all domesticates, and were selected during the initial episode of domestication of that animal or found, whereas improvement traits are nowadays only in a proportion of domesticates, though they may be fixed in private breeds or regional populations.[7] [8] [9]

The dog was the first domesticated species,[x] [11] [12] and was established across Eurasia before the terminate of the Late Pleistocene era, well before tillage and before the domestication of other animals.[11] The archaeological and genetic data suggest that long-term bidirectional gene flow between wild and domestic stocks – including donkeys, horses, New and Old Earth camelids, goats, sheep, and pigs – was common.[8] [13] Given its importance to humans and its value as a model of evolutionary and demographic change, domestication has attracted scientists from archaeology, paleontology, anthropology, botany, zoology, genetics, and the environmental sciences.[14] Among birds, the major domestic species today is the chicken, important for meat and eggs, though economically valuable poultry include the turkey, guineafowl and numerous other species. Birds are as well widely kept as cagebirds, from songbirds to parrots. The longest established invertebrate domesticates are the honey bee and the silkworm. Land snails are raised for food, while species from several phyla are kept for research, and others are bred for biological control.

The domestication of plants began at least 12,000 years ago with cereals in the Center East, and the bottle gourd in Asia. Agriculture developed in at to the lowest degree 11 different centres effectually the earth, domesticating different crops and animals.

Overview [edit]

Domestication, from the Latin domesticus , 'belonging to the house',[15] is "a sustained multi-generational, mutualistic relationship in which one organism assumes a significant degree of influence over the reproduction and intendance of some other organism in society to secure a more predictable supply of a resource of involvement, and through which the partner organism gains advantage over individuals that remain outside this relationship, thereby benefitting and often increasing the fitness of both the domesticator and the target domesticate."[one] [xvi] [17] [xviii] [19] This definition recognizes both the biological and the cultural components of the domestication process and the impacts on both humans and the domesticated animals and plants. All past definitions of domestication have included a human relationship between humans with plants and animals, but their differences lay in who was considered equally the lead partner in the relationship. This new definition recognizes a mutualistic human relationship in which both partners gain benefits. Domestication has vastly enhanced the reproductive output of ingather plants, livestock, and pets far beyond that of their wild progenitors. Domesticates have provided humans with resources that they could more predictably and deeply control, motion, and redistribute, which has been the advantage that had fueled a population explosion of the agro-pastoralists and their spread to all corners of the planet.[nineteen]

Houseplants and ornamentals are plants domesticated primarily for aesthetic enjoyment in and effectually the home, while those domesticated for large-scale food production are called crops. Domesticated plants deliberately contradistinct or selected for special desirable characteristics are cultigens. Animals domesticated for dwelling companionship are called pets, while those domesticated for nutrient or work are known as livestock.[ citation needed ]

This biological mutualism is not restricted to humans with domestic crops and livestock merely is well-documented in nonhuman species, especially amid a number of social insect domesticators and their plant and animal domesticates, for case the ant–fungus mutualism that exists between leafcutter ants and certain fungi.[i]

Domestication syndrome is the suite of phenotypic traits arising during domestication that distinguish crops from their wild ancestors.[6] [20] The term is as well applied to vertebrate animals, and includes increased docility and tameness, coat colour changes, reductions in tooth size, changes in craniofacial morphology, alterations in ear and tail grade (e.yard., floppy ears), more frequent and nonseasonal heat cycles, alterations in adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, inverse concentrations of several neurotransmitters, prolongations in juvenile behavior, and reductions in both total brain size and of particular encephalon regions.[21]

History [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. You tin help by adding to it. (February 2022) |

Cause and timing [edit]

Evolution of temperatures in the postglacial menstruation, after the Last Glacial Maximum, showing very low temperatures for the most part of the Younger Dryas, quickly rising later to reach the level of the warm Holocene, based on Greenland ice cores.[22]

The domestication of animals and plants was triggered by the climatic and environmental changes that occurred after the pinnacle of the Last Glacial Maximum around 21,000 years agone and which continue to this present day. These changes made obtaining food hard. The first domesticate was the wolf (Canis lupus) at least 15,000 years ago. The Younger Dryas that occurred 12,900 years ago was a period of intense cold and aridity that put pressure on humans to intensify their foraging strategies. Past the beginning of the Holocene from 11,700 years ago, favorable climatic atmospheric condition and increasing homo populations led to modest brute and constitute domestication, which allowed humans to augment the food that they were obtaining through hunter-gathering.[ii]

The Neolithic transition led to agronomical societies emerging in locations across Eurasia, Northward Africa, and South and Central America. In the Fertile Crescent 10,000-eleven,000 years ago, zooarchaeology indicates that goats, pigs, sheep, and taurine cattle were the start livestock to be domesticated. Ii m years later, humped zebu cattle were domesticated in what is today Baluchistan in Pakistan. In East Asia viii,000 years ago, pigs were domesticated from wild boar that were genetically different from those found in the Fertile Crescent. The horse was domesticated on the Central Asian steppe 5,500 years agone. Both the chicken in Southeast Asia and the cat in Arab republic of egypt were domesticated iv,000 years ago.[ii]

The sudden appearance of the domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) in the archaeological record then led to a rapid shift in the development, environmental, and demography of both humans and numerous species of animals and plants.[23] [8] It was followed by livestock and crop domestication, and the transition of humans from foraging to farming in different places and times across the planet.[23] [24] [25] Around 10,000 YBP, a new way of life emerged for humans through the direction and exploitation of plant and animate being species, leading to higher-density populations in the centers of domestication,[23] [26] the expansion of agricultural economies, and the evolution of urban communities.[23] [27]

Animals [edit]

Theory [edit]

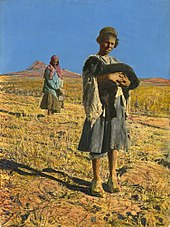

Karakul sheep[a] and shepherds in Iran. Photograph by Harold F. Weston, 1920s

The domestication of animals is the relationship between animals and humans who have influence on their "intendance" and reproduction.[1] Charles Darwin recognized the pocket-sized number of traits that made domestic species different from their wild ancestors. He was likewise the first to recognize the difference between conscious selective breeding in which humans directly select for desirable traits, and unconscious choice where traits evolve as a past-production of natural choice or from choice on other traits.[3] [4] [5]

There is a difference between domestic and wild populations, though studies suggest domestication equally a form of survival for near animals nether homo care. In that location is also such a difference between the domestication traits that researchers believe to have been essential at the early stages of domestication, and the improvement traits that have appeared since the split betwixt wild and domestic populations.[vi] [seven] [8] Domestication traits are mostly stock-still within all domesticates, and were selected during the initial episode of domestication of that animate being or plant, whereas improvement traits are present only in a proportion of domesticates, though they may be fixed in individual breeds or regional populations.[7] [eight] [nine]

Domestication of animals should non be confused with taming. Taming is the conditioned behavioral modification of an private animal, to reduce its natural avoidance of humans, and to tolerate the presence of humans. Domestication is the permanent genetic modification of a bred lineage that leads to an inherited predisposition to respond calmly to human being presence.[29] [30] [31]

Certain animal species, and sure individuals within those species, make better candidates for domestication merely for their disability to defend themselves. These animals showroom certain behavioral characteristics:[19] : Fig 1 [32] [33] [34]

- The size and arrangement of their social structure

- The availability and the caste of selectivity in their choice of mates

- The ease and speed with which the parents bail with their young, and the maturity and mobility of the young at birth

- The degree of flexibility in diet and habitat tolerance; and

- Responses to humans and new environments, including reduced flight response and reactivity to external stimuli.

Mammals [edit]

The beginnings of brute domestication involved a protracted coevolutionary procedure with multiple stages forth different pathways.[viii] There are iii proposed major pathways that near animal domesticates followed into domestication:

- commensals, adjusted to a human niche (e.1000., dogs, cats, perhaps pigs);

- prey animals sought for nutrient (e.grand., sheep, goats, cattle, h2o buffalo, yak, pig, reindeer, llama and alpaca); and

- animals targeted for typhoon and non-food resource (east.chiliad., horse, donkey, camel).[8] [thirteen] [19] [35] [36] [37] [38]

The dog was the first domesticant,[11] [12] and was established across Eurasia earlier the finish of the Belatedly Pleistocene era, well before cultivation and before the domestication of other animals.[xi] Humans did non intend to domesticate animals from either the commensal or prey pathways, or at least they did not envision a domesticated animal would result from information technology. In both of those cases, humans became entangled with these species equally the relationship between them intensified, and humans' role in their survival and reproduction led gradually to formalised animal husbandry.[eight] Although the directed pathway proceeded from capture to taming, the other two pathways are not as goal-oriented, and archaeological records advise that they took place over much longer time frames.[14]

Dissimilar other domestic species which were primarily selected for product-related traits, dogs were initially selected for their behaviors.[39] [40] The archaeological and genetic data suggest that long-term bidirectional cistron flow between wild and domestic stocks – including donkeys, horses, New and Old World camelids, goats, sheep, and pigs – was common.[8] [thirteen] One study has concluded that homo selection for domestic traits probable counteracted the homogenizing effect of gene flow from wild boars into pigs and created domestication islands in the genome. The aforementioned procedure may also use to other domesticated animals.[41] [42]

Birds [edit]

Domesticated birds principally mean poultry, raised for meat and eggs:[43] some Galliformes (chicken, turkey, guineafowl) and Anseriformes (waterfowl: duck, goose, swan). Also widely domesticated are cagebirds such as songbirds and parrots; these are kept both for pleasure and for use in research.[44] The domestic pigeon has been used both for nutrient and as a means of communication between far-flung places through the exploitation of the dove's homing instinct; research suggests it was domesticated equally early as 10,000 years ago.[45] Craven fossils in China were dated seven,400 years agone. The craven's wild antecedent is Gallus gallus, the red junglefowl of Southeast Asia. It appears to take been kept initially for cockfighting rather than for food.[46]

Invertebrates [edit]

Two insects, the silkworm and the western dear bee, take been domesticated for over 5,000 years, frequently for commercial use. The silkworm is raised for the silk threads wound around its pupal cocoon; the western honey bee, for honey, and, lately, for pollination of crops.[47]

Several other invertebrates accept been domesticated, both terrestrial and aquatic, including some such as Drosophila melanogaster fruit flies and the freshwater cnidarian Hydra for research into genetics and physiology. Few accept a long history of domestication. Most are used for nutrient or other products such every bit shellac and cochineal. The phyla involved are Cnidaria, Platyhelminthes (for biological control), Annelida, Mollusca, Arthropoda (marine crustaceans too as insects and spiders), and Echinodermata. While many marine molluscs are used for food, only a few have been domesticated, including squid, cuttlefish and octopus, all used in research on behaviour and neurology. Terrestrial snails in the genera Helix and Murex are raised for nutrient. Several parasitic or parasitoidal insects including the fly Eucelatoria, the beetle Chrysolina, and the wasp Aphytis are raised for biological control. Conscious or unconscious artificial pick has many effects on species nether domestication; variability can readily be lost by inbreeding, option against undesired traits, or genetic drift, while in Drosophila, variability in eclosion time (when adults emerge) has increased.[48]

Plants [edit]

The initial domestication of animals impacted near on the genes that controlled their behavior, merely the initial domestication of plants impacted most on the genes that controlled their morphology (seed size, constitute architecture, dispersal mechanisms) and their physiology (timing of germination or ripening).[nineteen] [25]

The domestication of wheat provides an example. Wild wheat shatters and falls to the basis to reseed itself when ripe, but domesticated wheat stays on the stalk for easier harvesting. This change was possible because of a random mutation in the wild populations at the beginning of wheat'southward cultivation. Wheat with this mutation was harvested more oftentimes and became the seed for the next crop. Therefore, without realizing, early farmers selected for this mutation. The result is domesticated wheat, which relies on farmers for its reproduction and broadcasting.[49]

History [edit]

Farmers with wheat and cattle – Ancient Egyptian art 3,400 years ago

The earliest human being attempts at plant domestication occurred in the Center Eastward. There is early on evidence for conscious tillage and trait selection of plants by pre-Neolithic groups in Syrian arab republic: grains of rye with domestic traits dated thirteen,000 years agone have been recovered from Abu Hureyra in Syria,[50] simply this appears to exist a localised phenomenon resulting from cultivation of stands of wild rye, rather than a definitive step towards domestication.[50]

The bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria) plant, used as a container before the advent of ceramic engineering science, appears to have been domesticated 10,000 years ago. The domesticated bottle gourd reached the Americas from Asia by 8,000 years ago, most likely due to the migration of peoples from Asia to America.[51]

Cereal crops were starting time domesticated around 11,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East. The start domesticated crops were mostly annuals with large seeds or fruits. These included pulses such as peas and grains such as wheat. The Centre East was especially suited to these species; the dry-summer climate was conducive to the evolution of big-seeded annual plants, and the diversity of elevations led to a great variety of species. As domestication took place humans began to move from a hunter-gatherer society to a settled agricultural order. This change would eventually pb, some 4000 to 5000 years later, to the get-go city states and eventually the ascent of civilization itself.

Connected domestication was gradual, a process of intermittent trial and fault, and ofttimes resulted in diverging traits and characteristics.[52] Over time perennials and small trees including the apple and the olive were domesticated. Some plants, such as the macadamia nut and the pecan, were non domesticated until recently.

In other parts of the earth very different species were domesticated. In the Americas squash, maize, beans, and peradventure manioc (also known as cassava) formed the core of the diet. In East asia millet, rice, and soy were the virtually important crops. Some areas of the world such every bit Southern Africa, Australia, California and southern South America never saw local species domesticated.

Differences from wild plants [edit]

Domesticated plants may differ from their wild relatives in many means, including

- the way they spread to a more diverse environment and have a wider geographic range;[53]

- unlike ecological preference (sun, water, temperature, nutrients, etc. requirements), different disease susceptibility;

- conversion from a perennial to annual;

- loss of seed dormancy and photoperiodic controls;

- simultaneous flower and fruit, double flowers;

- a lack of shattering or scattering of seeds, or even loss of their dispersal mechanisms completely;

- less efficient breeding system (e.grand. lack normal pollinating organs, making human intervention a requirement), smaller seeds with lower success in the wild, or even consummate sexual sterility (eastward.g. seedless fruits) and therefore only vegetative reproduction;

- less defensive adaptations such as hairs, thorns, spines, and prickles, poison, protective coverings and sturdiness, rendering them more probable to exist eaten by animals and pests unless cared by humans;

- chemical limerick, giving them better palatability (e.chiliad. carbohydrate content), improve smell, and lower toxicity;[54]

- edible role larger, and easier separated from non-edible office (e.thou. freestone fruit).

The touch of domestication on the found microbiome [edit]

A conceptual figure on the impact of domestication on the plant endophytic microbiome. (a) A phylogenetic altitude amongst Malus species which contains wild species (blackness branches) and progenitor wild species (blueish branches). The extended green co-operative represents Malus domestica with its close affiliation its main ancestor (Thousand. sieversii). Dashed lines indicate introgression events between Malus progenitors which contributed to the formation of Grand. domestica. (b) The predicted three scenarios: Scenario 1, reduction in species diversity due to loss in microbial species; Scenario 2, increase in microbial diversity due to introgressive hybridization during the apple domestication; Scenario three, diversity was not afflicted past domestication.[55]

The microbiome, divers every bit the collection of microorganisms inhabiting the surface and internal tissue of plants, has been shown to be afflicted past plant domestication and breeding. This includes variation the microbial customs composition [56] [57] [55] to change in the number of microbial species associated with plants, i.e., species multifariousness.[58] [55] Testify also bear witness that plant lineage, including speciation, domestication, and convenance accept shaped the plant endophytes in similar patterns as plant genes.[55] Such patterns are also known as phylosymbiosis which have been observed in several brute and plant lineages.[59] [60] [61]

Traits that are being genetically improved [edit]

There are many challenges facing modern farmers, including climate change, pests, soil salinity, drought, and periods with express sunlight.[62]

Drought is one of the most serious challenges facing farmers today. With shifting climates comes shifting weather patterns, significant that regions that could traditionally rely on a substantial amount of precipitation were, quite literally, left out to dry. In low-cal of these weather condition, drought resistance in major crop plants has become a articulate priority.[63] One method is to identify the genetic ground of drought resistance in naturally drought resistant plants, i.e. the Bambara groundnut. Next, transferring these advantages to otherwise vulnerable crop plants. Rice, which is ane of the most vulnerable crops in terms of drought, has been successfully improved by the addition of the Barley hva1 gene into the genome using transgenetics. Drought resistance tin can too exist improved through changes in a plant'due south root organization architecture,[64] such as a root orientation that maximizes water retention and food uptake. There must be a continued focus on the efficient usage of available water on a planet that is expected to have a population in excess of ix-billion people by 2050.

Another specific expanse of genetic improvement for domesticated crops is the crop constitute's uptake and utilization of soil potassium, an essential element for crop plants yield and overall quality. A plant's power to effectively uptake potassium and utilize information technology efficiently is known as its potassium utilization efficiency.[65] It has been suggested that commencement optimizing plant root architecture and and then root potassium uptake action may effectively amend institute potassium utilization efficiency.

Crop plants that are being genetically improved [edit]

Cereals, rice, wheat, corn, sorghum and barley, make up a huge amount of the global diet across all demographic and social scales. These cereal crop plants are all autogamous, i.e. self-fertilizing, which limits overall diversity in allelic combinations, and therefore adaptability to novel environments.[66] To gainsay this effect the researchers propose an "Isle Model of Genomic Selection". By breaking a unmarried large population of cereal ingather plants into several smaller sub-populations which tin receive "migrants" from the other subpopulations, new genetic combinations tin be generated.

The Bambara groundnut is a durable crop found that, like many underutilized crops, has received piddling attention in an agricultural sense. The Bambara Groundnut is drought resistant and is known to exist able to abound in well-nigh any soil conditions, no thing how impoverished an surface area may exist. New genomic and transcriptomic approaches are allowing researchers to meliorate this relatively pocket-size-scale crop, as well as other big-scale ingather plants.[67] The reduction in cost, and broad availability of both microarray technology and Next Generation Sequencing accept fabricated it possible to analyze underutilized crops, like the groundnut, at genome-wide level. Non overlooking particular crops that don't appear to hold any value exterior of the developing world will be key to non merely overall crop improvement, but too to reducing the global dependency on only a few crop plants, which holds many intrinsic dangers to the global population'south food supply.[67]

Challenges facing genetic comeback [edit]

The semi-barren torrid zone, ranging from parts of North and South Africa, Asia particularly in the Due south Pacific, all the mode to Australia are notorious for being both economically destitute and agriculturally hard to cultivate and subcontract effectively. Barriers include everything from lack of rainfall and diseases, to economic isolation and ecology irresponsibility.[68] There is a large interest in the continued efforts, of the International Crops Research Found for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRSAT) to ameliorate staple foods. some mandated crops of ICRISAT include the groundnut, pigeonpea, chickpea, sorghum and pearl millet, which are the master staple foods for about one billion people in the semi-arid tropics.[69] As office of the ICRISAT efforts, some wild plant breeds are being used to transfer genes to cultivated crops by interspecific hybridization involving modern methods of embryo rescue and tissue civilization.[70] One example of early on success has been work to combat the very detrimental peanut dodder virus. Transgenetic plants containing the glaze protein gene for resistance against peanut clump virus have already been produced successfully.[69] Some other region threatened by food security are the Pacific Isle Countries, which are disproportionally faced with the negative effects of climatic change. The Pacific Islands are largely made up of a concatenation of small bodies of land, which obviously limits the amount of geographical area in which to farm. This leaves the region with only two viable options ane.) increase agricultural production or 2.) increase food importation. The latter of course runs into the issues of availability and economic feasibility, leaving only the first option as a viable means to solve the region'due south food crisis. It is much easier to misuse the limited resources remaining, as compared with solving the problem at its cadre.[71]

Working with wild plants to improve domestics [edit]

Work has likewise has been focusing on improving domestic crops through the use of crop wild relatives.[69] The amount and depth of genetic material available in ingather wild relatives is larger than originally believed, and the range of plants involved, both wild and domestic, is always expanding.[72] Through the use of new biotechnological tools such as genome editing, cisgenesis/intragenesis, the transfer of genes between crossable donor species including hybrids, and other omic approaches.[72]

Wild plants tin be hybridized with ingather plants to course perennial crops from annuals, increase yield, growth rate, and resistance to outside pressures like disease and drought.[73] Importantly, these changes take significant lengths of time to attain, sometimes fifty-fifty decades. However, the outcome can be extremely successful as is the instance with a hybrid grass variant known as Kernza. [73] Over the course of nearly three decades, piece of work was washed on an attempted hybridization between an already domesticated grass strain, and several of its wild relatives. The domesticated strain as was more compatible in its orientation, but the wild strains were larger and propagated faster. The resulting Kernza crop has traits from both progenitors: uniform orientation and a linearly vertical root organization from the domesticated crop, forth with increased size and rate of propagation from the wild relatives.[73]

Fungi and micro-organisms [edit]

Several species of fungi have been domesticated for use directly as food, or in fermentation to produce foods and drugs. The white button mushroom Agaricus bisporus is widely grown for food.[74] The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae accept been used for thousands of years to ferment beer and wine, and to leaven bread.[75] Mould fungi including Penicillium are used to mature cheeses and other dairy products, as well equally to make drugs such equally antibiotics.[76]

Furnishings [edit]

On domestic animals [edit]

Selection of animals for visible "desirable" traits may take undesired consequences. Captive and domesticated animals oft have smaller size, piebald color, shorter faces with smaller and fewer teeth, diminished horns, weak musculus ridges, and less genetic variability. Poor joint definition, late fusion of the limb os epiphyses with the diaphyses, hair changes, greater fatty accumulation, smaller brains, simplified beliefs patterns, extended immaturity, and more pathology are amongst the defects of domestic animals. All of these changes have been documented by archaeological evidence, and confirmed by fauna breeders in the 20th century.[77] In 2014, a study proposed the theory that under selection, docility in mammals and birds results partly from a slowed pace of neural crest development, that would in turn cause a reduced fright–startle response due to mild neurocristopathy that causes domestication syndrome. The theory was unable to explain curly tails nor domestication syndrome exhibited past plants.[21]

A side event of domestication has been zoonotic diseases. For example, cattle accept given humanity various viral poxes, measles, and tuberculosis; pigs and ducks have given influenza; and horses have given the rhinoviruses. Many parasites have their origins in domestic animals.[4] [ page needed ] The appearance of domestication resulted in denser human populations which provided ripe conditions for pathogens to reproduce, mutate, spread, and eventually notice a new host in humans.[78]

Paul Shepard writes "Man substitutes controlled breeding for natural selection; animals are selected for special traits like milk production or passivity, at the expense of overall fitness and nature-wide relationships...Though domestication broadens the diverseness of forms – that is, increases visible polymorphism – it undermines the crisp demarcations that dissever wild species and cripples our recognition of the species as a group. Knowing only domestic animals dulls our understanding of the mode in which unity and discontinuity occur equally patterns in nature, and substitutes an attention to individuals and breeds. The wide diversity of size, colour, shape, and form of domestic horses, for example, blurs the distinction among dissimilar species of Equus that in one case were constant and meaningful."[79]

On society [edit]

Jared Diamond in his volume Guns, Germs, and Steel describes the universal tendency for populations that take acquired agriculture and domestic animals to develop a large population and to expand into new territories. He recounts migrations of people armed with domestic crops overtaking, displacing or killing indigenous hunter-gatherers,[four] : 112 whose lifestyle is coming to an end.[4] : 86

Some anarcho-primitivist authors describe domestication as the process past which previously nomadic homo populations shifted towards a sedentary or settled being through agriculture and animal husbandry. They merits that this kind of domestication demands a totalitarian human relationship with both the land and the plants and animals existence domesticated. They say that whereas, in a state of wildness, all life shares and competes for resource, domestication destroys this balance. Domesticated landscape (e.g. pastoral lands/agronomical fields and, to a bottom caste, horticulture and gardening) ends the open sharing of resources; where "this was everyone's", information technology is now "mine". Anarcho-primitivists land that this notion of ownership laid the foundation for social hierarchy as property and power emerged. It also involved the destruction, enslavement, or assimilation of other groups of early people who did not make such a transition.[80]

Under the framework of Dialectical naturalism, Murray Bookchin has argued that the bones notion of domestication is incomplete: That, since the domestication of animals is a crucial development within homo history, it can also be understood as the domestication of humanity itself in turn. Under this dialectical framework, domestication is always a 'two-way street' with both parties being unavoidably altered by their relationship with each other.[81]

David Nibert, professor of sociology at Wittenberg University, posits that the domestication of animals, which he refers to as "domesecration" equally information technology often involved extreme violence against animal populations and the devastation of the environment, resulted in the corruption of human ethics, and helped pave the way for societies steeped in "conquest, extermination, displacement, repression, coerced and enslaved servitude, gender subordination and sexual exploitation, and hunger."[82]

On diversity [edit]

Industrialized wheat harvest – North America today

In 2016, a report establish that humans accept had a major impact on global genetic diversity besides as extinction rates, including a contribution to megafaunal extinctions. Pristine landscapes no longer be and have non existed for millennia, and humans have concentrated the planet's biomass into human-favored plants and animals. Domesticated ecosystems provide nutrient, reduce predator and natural dangers, and promote commerce, just take also resulted in habitat loss and extinctions commencing in the Tardily Pleistocene. Ecologists and other researchers are brash to make better use of the archaeological and paleoecological data available for gaining an understanding the history of man impacts before proposing solutions.[83]

See also [edit]

- Animal–industrial complex

- Anthrozoology

- Columbian Exchange

- Domestication theory

- Experimental evolution

- Genetic technology

- Genetic erosion

- Genomics of domestication

- History of establish breeding

- Marking assisted selection

- Pet

- Self-domestication

- Timeline of agronomics and food technology

- Wild ancestors

Notes [edit]

- ^ This Primal Asian breed is ancient, dating perhaps to 1400 BCE.[28]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Zeder, M.A. (2015). "Core questions in domestication Research". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (eleven): 3191–98. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.3191Z. doi:ten.1073/pnas.1501711112. PMC4371924. PMID 25713127.

- ^ a b c McHugo, Gillian P.; Dover, Michael J.; Machugh, David E. (2019). "Unlocking the origins and biology of domestic animals using ancient DNA and paleogenomics". BMC Biological science. 17 (1): 98. doi:10.1186/s12915-019-0724-seven. PMC6889691. PMID 31791340.

- ^ a b Darwin, Charles (1868). The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. London: John Murray. OCLC 156100686.

- ^ a b c d eastward Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: A brusk history of everybody for the last 13,000 years. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN978-0-09-930278-0.

- ^ a b Larson, G.; Piperno, D.R.; Allaby, R.G.; Purugganan, M.D.; Andersson, Fifty.; Arroyo-Kalin, M.; Barton, L.; Climer Vigueira, C.; Denham, T.; Dobney, Chiliad.; Doust, A.Northward.; Gepts, P.; Gilbert, M.T. P.; Gremillion, Thou.J.; Lucas, 50.; Lukens, L.; Marshall, F.B.; Olsen, M.M.; Pires, J. C.; Richerson, P.J.; Rubio De Casas, R.; Sanjur, O.I.; Thomas, M.G.; Fuller, D. Q. (2014). "Current perspectives and the future of domestication studies". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 111 (17): 6139–46. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6139L. doi:ten.1073/pnas.1323964111. PMC4035915. PMID 24757054.

- ^ a b c Olsen, K.Thousand.; Wendel, J.F. (2013). "A bountiful harvest: genomic insights into crop domestication phenotypes". Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64: 47–70. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120048. PMID 23451788. S2CID 727983.

- ^ a b c d Doust, A.Northward.; Lukens, Fifty.; Olsen, 1000.M.; Mauro-Herrera, M.; Meyer, A.; Rogers, Thousand. (2014). "Beyond the single gene: How epistasis and factor-past-environment effects influence ingather domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (17): 6178–83. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6178D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308940110. PMC4035984. PMID 24753598.

- ^ a b c d eastward f grand h i j Larson, G. (2014). "The Evolution of Animal Domestication" (PDF). Almanac Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 45: 115–36. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135813.

- ^ a b Meyer, Rachel S.; Purugganan, Michael D. (2013). "Development of crop species: Genetics of domestication and diversification". Nature Reviews Genetics. 14 (12): 840–52. doi:10.1038/nrg3605. PMID 24240513. S2CID 529535.

- ^ "Domestication". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Larson, G. (2012). "Rethinking dog domestication past integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (23): 8878–8883. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8878L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203005109. PMC3384140. PMID 22615366.

- ^ a b Perri, Angela (2016). "A wolf in dog's clothing: Initial dog domestication and Pleistocene wolf variation". Journal of Archaeological Scientific discipline. 68: one–four. doi:ten.1016/j.jas.2016.02.003.

- ^ a b c Marshall, F. (2013). "Evaluating the roles of directed breeding and gene flow in animal domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the Usa of America. 111 (17): 6153–6158. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6153M. doi:x.1073/pnas.1312984110. PMC4035985. PMID 24753599.

- ^ a b Larson, G. (2013). "A population genetics view of beast domestication" (PDF). Trends in Genetics. 29 (4): 197–205. doi:x.1016/j.tig.2013.01.003. PMID 23415592.

- ^ "Domesticate". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. 2014.

- ^ Lorenzo Maggioni (2015) Domestication of Brassica oleracea L., Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae, p. 38

- ^ Zeder, Thousand. (2014). "Domestication: Definition and Overview". In Smith, Claire (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 2184–94. doi:10.1007/978-i-4419-0465-2_71. ISBN978-1-4419-0426-3.

- ^ Sykes, N. (2014). "Beast Revolutions". Beastly Questions: Animal Answers to Archaeological Issues. Bloomsbury Bookish. pp. 25–26. ISBN978-one-4725-0624-v.

- ^ a b c d due east Zeder, G.A. (2012). "The domestication of animals". Journal of Anthropological Research. 68 (two): 161–xc. doi:ten.3998/jar.0521004.0068.201. S2CID 85348232.

- ^ Hammer, K. (1984). "Das Domestikationssyndrom". Kulturpflanze. 32: 11–34. doi:ten.1007/bf02098682. S2CID 42389667.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Adam S.; Wrangham, Richard Due west.; Fitch, W. Tecumseh (July 2014). "The 'Domestication Syndrome' in Mammals: A Unified Explanation Based on Neural Crest Cell Beliefs and Genetics" (PDF). Genetics. 197 (3): 795–808. doi:x.1534/genetics.114.165423. PMC4096361. PMID 25024034.

- ^ Zalloua, Pierre A.; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (Jan 6, 2017). "Mapping Mail service-Glacial expansions: The Peopling of Southwest asia". Scientific Reports. 7: 40338. Bibcode:2017NatSR...740338P. doi:x.1038/srep40338. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC5216412. PMID 28059138.

- ^ a b c d Machugh, David E.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (2016). "Taming the By: Ancient Deoxyribonucleic acid and the Study of Animal Domestication". Annual Review of Creature Biosciences. 5: 329–351. doi:x.1146/annurev-creature-022516-022747. PMID 27813680. S2CID 21991146.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Willcox, George; Allaby, Robin Thou. (2011). "Cultivation and domestication had multiple origins: arguments against the core expanse hypothesis for the origins of agriculture in the Virtually East". World Archaeology. 43 (4): 628–652. doi:10.1080/00438243.2011.624747. S2CID 56437102.

- ^ a b Zeder, M.A. 2006. "Archaeological approaches to documenting brute domestication". In Documenting Domestication: New Genetic and Archaeological Paradigms, eds. K.A. Zeder, D.G. Bradley, E. Emshwiller, B.D. Smith, pp. 209–27. Berkeley: Univ. Calif. Printing

- ^ Bocquet-Appel, J.P. (2011). "When the earth'south population took off: the springboard of the Neolithic Demographic Transition". Scientific discipline. 333 (6042): 560–61. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..560B. doi:10.1126/science.1208880. PMID 21798934. S2CID 29655920.

- ^ Barker G. 2006. The Agronomical Revolution in Prehistory: Why Did Foragers Go Farmers? Oxford:Oxford Univ. Press

- ^ "Karakul". Breeds of Livestock. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Cost, Edward O. (2008). Principles and applications of domestic animal behavior: an introductory text. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-1-78064-055-6 . Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Driscoll, C.A.; MacDonald, D.W.; O'Brien, S.J. (2009). "From wild fauna to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106: 9971–78. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9971D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901586106. PMC2702791. PMID 19528637.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2012). "Chapter ane". In Gepts, P. (ed.). Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Evolution, and Sustainability. Cambridge University Printing. p. thirteen.

- ^ Unhurt, Due east.B. 1969. "Domestication and the evolution of behavior," in The behavior of domestic animals, second edition. Edited by E.Southward.E. Hafez, pp. 22–42. London: Bailliere, Tindall, and Cassell

- ^ Cost, Edward O. (1984). "Behavioral aspects of beast domestication". Quarterly Review of Biology. 59 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1086/413673. JSTOR 2827868. S2CID 83908518.

- ^ Toll, Edward O. (2002). Animal domestication and behavior (PDF). Wallingford, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: CABI Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2017. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Frantz, L. (2015). "The Evolution of Suidae". Annual Review of Brute Biosciences. 4: 61–85. doi:10.1146/annurev-animate being-021815-111155. PMID 26526544.

- ^ Blaustein, R. (2015). "Unraveling the Mysteries of Animal Domestication:Whole-genome sequencing challenges sometime assumptions". BioScience. 65 (one): 7–13. doi:10.1093/biosci/biu201.

- ^ Vahabi, Yard. (2015). "Human being species as the principal predator". The Political Economic system of Predation: Manhunting and the Economic science of Escape. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN978-1-107-13397-6.

- ^ Paul Gepts, ed. (2012). "nine". Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Development, and Sustainability. Cambridge University Press. pp. 227–59.

- ^ Serpell J, Duffy D. "Domestic dog Breeds and Their Behavior". In: Domestic dog Cognition and Behavior. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014

- ^ Cagan, Alex; Blass, Torsten (2016). "Identification of genomic variants putatively targeted by pick during domestic dog domestication". BMC Evolutionary Biology. sixteen: 10. doi:x.1186/s12862-015-0579-7. PMC4710014. PMID 26754411.

- ^ Frantz, Fifty. (2015). "Testify of long-term gene menstruation and selection during domestication from analyses of Eurasian wild and domestic pig genomes". Nature Genetics. 47 (10): 1141–48. doi:ten.1038/ng.3394. PMID 26323058. S2CID 205350534.

- ^ Pennisi, E (2015). "The taming of the pig took some wild turns". Science. doi:x.1126/science.aad1692.

- ^ "Poultry". The American Heritage: Dictionary of the English Language. Vol. 4th edition. Houghton Mifflin Visitor. 2009.

- ^ "Avicultural Social club of America". Avicultural Society of America. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Blechman, Andrew (2007). Pigeons – The fascinating saga of the world'south most revered and reviled bird. Academy of Queensland Press. ISBN978-0-7022-3641-ix.

- ^ Lawler, Andrew; Adler, Jerry (June 2012). "How the Chicken Conquered the Globe". Smithsonian Mag (June 2012).

- ^ Bailey, Leslie; Brawl, B.V. (2013). Honey Bee Pathology. Elsevier. pp. 7–8. ISBN978-ane-4832-8809-three.

- ^ Gon Three, Samuel M.; Price, Edward O. (October 1984). "Invertebrate Domestication: Behavioral Considerations". BioScience. 34 (9): 575–79. doi:x.2307/1309600. JSTOR 1309600.

- ^ Zohary, D.; Hopf, M. (2000). Domestication of Plants in the Old World Oxford University Press.[ folio needed ]

- ^ a b Hillman, G.; Hedges, R.; Moore, A.; Colledge, S.; Pettitt, P. (2001). "New evidence of Lateglacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates". Holocene. 11 (four): 383–93. Bibcode:2001Holoc..eleven..383H. doi:10.1191/095968301678302823. S2CID 84930632.

- ^ Erickson, D.L.; Smith, B.D.; Clarke, A.C.; Sandweiss, D.H.; Tuross, N. (December 2005). "An Asian origin for a 10,000-year-erstwhile domesticated plant in the Americas". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (51): 18315–20. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10218315E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509279102. PMC1311910. PMID 16352716.

- ^ Hughes, Aoife; Oliveira, Hour; Fradgley, Northward; Corke, F; Cockram, J; Doonan, JH; Nibau, C (March 14, 2019). "μCT trait analysis reveals morphometric differences between domesticated temperate pocket-size grain cereals and their wild relatives". The Plant Periodical. 99 (ane): 98–111. doi:ten.1111/tpj.14312. PMC6618119. PMID 30868647.

- ^ Zeven, A.C.; de Wit, J. M. (1982). Dictionary of Cultivated Plants and Their Regions of Diversity, Excluding Virtually Ornamentals, Forest Trees and Lower Plants. Wageningen, Netherlands: Eye for Agronomical Publishing and Documentation.

- ^ Wu, Yuye; Guo, Tingting; Mu, Qi; Wang, Jinyu; Li, Xin; Wu, Yun; Tian, Bin; Wang, Ming Li; Bai, Guihua; Perumal, Ramasamy; Fob, Harold N. (December 2019). "Allelochemicals targeted to rest competing selections in African agroecosystems". Nature Plants. 5 (12): 1229–1236. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0563-0. ISSN 2055-0278. PMID 31792396. S2CID 208539527.

- ^ a b c d Abdelfattah, Ahmed; Tack, Ayco J. Yard.; Wasserman, Birgit; Liu, Jia; Berg, Gabriele; Norelli, John; Droby, Samir; Wisniewski, Michael (2021). "Bear witness for host–microbiome co-evolution in apple tree". New Phytologist. 234 (vi): 2088–2100. doi:x.1111/nph.17820. ISSN 1469-8137. PMID 34823272. S2CID 244661193.

- ^ Mutch, Lesley A.; Young, J. Peter W. (2004). "Multifariousness and specificity of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae on wild and cultivated legumes". Molecular Ecology. thirteen (8): 2435–2444. doi:x.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02259.x. ISSN 1365-294X. PMID 15245415. S2CID 1123490.

- ^ Kiers, E. Toby; Hutton, Mark G; Denison, R. Ford (Dec 22, 2007). "Man selection and the relaxation of legume defences confronting ineffective rhizobia". Proceedings of the Royal Social club B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1629): 3119–3126. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1187. PMC2293947. PMID 17939985.

- ^ Coleman-Derr, Devin; Desgarennes, Damaris; Fonseca-Garcia, Citlali; Gross, Stephen; Clingenpeel, Scott; Woyke, Tanja; North, Gretchen; Visel, Axel; Partida-Martinez, Laila P.; Tringe, Susannah G. (2016). "Constitute compartment and biogeography affect microbiome composition in cultivated and native Agave species". New Phytologist. 209 (2): 798–811. doi:ten.1111/nph.13697. ISSN 1469-8137. PMC5057366. PMID 26467257.

- ^ Bouffaud, Marie-Lara; Poirier, Marie-Andrée; Muller, Daniel; Moënne-Loccoz, Yvan (2014). "Root microbiome relates to plant host evolution in maize and other Poaceae". Environmental Microbiology. 16 (ix): 2804–2814. doi:ten.1111/1462-2920.12442. ISSN 1462-2920. PMID 24588973.

- ^ Abdullaeva, Yulduzkhon; Ambika Manirajan, Binoy; Honermeier, Bernd; Schnell, Sylvia; Cardinale, Massimiliano (July 1, 2021). "Domestication affects the composition, diverseness, and co-occurrence of the cereal seed microbiota". Journal of Advanced Enquiry. 31: 75–86. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2020.12.008. ISSN 2090-1232. PMC8240117. PMID 34194833.

- ^ Favela, Alonso; O. Bohn, Martin; D. Kent, Angela (August 2021). "Maize germplasm chronosequence shows ingather breeding history impacts recruitment of the rhizosphere microbiome". The ISME Journal. 15 (viii): 2454–2464. doi:ten.1038/s41396-021-00923-z. ISSN 1751-7370. PMC8319409. PMID 33692487.

- ^ Horton, Peter (2000). "Prospects for ingather improvement through the genetic manipulation of photosynthesis: morphological and biochemical aspects of light capture". Journal of Experimental Botany. 51: 475–85. doi:x.1093/jexbot/51.suppl_1.475. JSTOR 23696526. PMID 10938855.

- ^ Mitra, Jiban (2001). "Genetics and genetic improvement of drought resistance in crop plants". Current Science. lxxx (vi): 758–63. JSTOR 24105661.

- ^ Forester; et al. (2007). "Root organisation architecture: Opportunities and constraints for genetic improvement of crops". Trends in Plant Science. 12 (10): 474–81. doi:x.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.012. PMID 17822944.

- ^ Wang, Yi; Wu, Wei-Hua (2015). "Genetic approaches for comeback of the crop potassium acquisition and utilization efficiency". Current Opinion in Establish Biology. 25: 46–52. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2015.04.007. PMID 25941764.

- ^ Shion, Yabe; et al. (2016). "Island-model Genomic Pick for Long-term Genetic Improvement of Autogamous Crops". PLOS ONE. eleven (iv): e0153945. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1153945Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153945. PMC4846018. PMID 27115872.

- ^ a b Khan, F; Azman, R; Chai, H.H; Mayes, S; Lu, C (2016). "Genomic and transcriptomic approaches towards the genetic improvement of an underutilized crops: the case of bambara groundnut". African Crop Scientific discipline Journal. 24 (4): 429–58. doi:10.4314/acsj.v24i4.ix.

- ^ Sharma, Kiran K.; Ortiz, Rodomiro (2000). "Program for the Awarding of Genetic Transformation for Crop Improvement in the Semi-Arid Torrid zone" (PDF). In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. 36 (2): 83–92. doi:10.1007/s11627-000-0019-1. S2CID 10072809.

- ^ a b c Zhang, Hengyou; Mittal, Neha; Leamy, Larry J.; Barazani, Oz; Song, Bao-Hua (2016). "Back into the wild – Apply untapped genetic diversity of wild relatives for crop improvement". Evolutionary Applications. x (ane): five–24. doi:10.1111/eva.12434. PMC5192947. PMID 28035232.

- ^ Kilian, B.; et al. (2010). "Accessing genetic diversity for crop improvement" (PDF). Electric current Opinion in Plant Biology. thirteen (2): 167–73. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2010.01.004. PMID 20167531.

- ^ Lebot, Vincent (December 2013). "Coping with insularity: The need for crop genetic comeback to strengthen accommodation to climate change and food security in the Pacific". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 15 (6): 1405–23. doi:10.1007/s10668-013-9445-ane. S2CID 154550463.

- ^ a b Morrell, Peter; et al. (2007). "Plant Domestication, a Unique Opportunity to Identify the Genetic Basis of Adaptation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (Suppl 1): 8641–48. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8641R. doi:x.1073/pnas.0700643104. PMC1876441. PMID 17494757.

- ^ a b c van Tassel, D.; DeHann, 50. (2013). "Wild plants to the rescue: efforts to domesticate new, high-Yield, perennial grain crops require patience and persistence – but such plants could transform agriculture". American Scientist.

- ^ "Agaricus bisporus:The Button Mushroom". MushroomExpert.com. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Legras, Jean-Luc; Merdinoglu, Didier; Cornuet, Jean-Marie; Karst, Francis (2007). "Staff of life, beer and wine: Saccharomyces cerevisiae diverseness reflects human history". Molecular Ecology. xvi (10): 2091–102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03266.x. PMID 17498234. S2CID 13157807.

- ^ "Pfizer's work on penicillin for World War II becomes a National Celebrated Chemical Landmark". American Chemical Society. June 12, 2008.

- ^ Berry, R.J. (1969). "The Genetical Implications of Domestication in Animals". In Ucko, Peter J.; Dimbleby, M.W. (eds.). The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals. Chicago: Aldine. pp. 207–17.

- ^ Caldararo, Niccolo Leo (2012). "Evolutionary Aspects of Affliction Avoidance: The Role of Affliction in the Evolution of Complex Society". SSRN Working Paper Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2001098. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 87639702.

- ^ Shepard, Paul (1973). "Affiliate One: Ten Thousand Years of Crisis". The Tender Carnivore and the Sacred Game. University of Georgia Press. pp. x–11.

- ^ Boyden, Stephen Vickers (1992). "Biohistory: The coaction between homo society and the biosphere, past and present". Man and the Biosphere Series. 8 (supplement 173): 665. Bibcode:1992EnST...26..665.. doi:x.1021/es00028a604.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. The Philosophy of Social Ecology, p. 85-seven.

- ^ Nibert, David (2013). Beast Oppression and Human being Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict. Columbia Academy Printing. pp. 1–5. ISBN978-0231151894.

- ^ Boivin, Nicole L.; Zeder, Melinda A.; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Crowther, Alison; Larson, Greger; Erlandson, Jon M.; Denham, Tim; Petraglia, Michael D. (2016). "Ecological consequences of human niche construction: Examining long-term anthropogenic shaping of global species distributions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (23): 6388–96. doi:10.1073/pnas.1525200113. PMC4988612. PMID 27274046.

Further reading [edit]

- Halcrow, South.E.; Harris, Northward.J.; Tayles, N.; Ikehara-Quebral, R.; Pietrusewsky, M. (2013). "From the mouths of babes: Dental caries in infants and children and the intensification of agriculture in mainland Southeast Asia". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 150 (iii): 409–twenty. doi:x.1002/ajpa.22215. PMID 23359102.

- Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods, "Survival of the Friendliest: Natural choice for hypersocial traits enabled Earth's apex species to best Neandertals and other competitors", Scientific American, vol. 323, no. ii (August 2020), pp. 58–63.

- Hayden, B. (2003). "Were luxury foods the showtime domesticates? Ethnoarchaeological perspectives from Southeast Asia". World Archaeology. 34 (3): 458–69. doi:10.1080/0043824021000026459a. S2CID 162526285.

- Marciniak, Arkadiusz (2005). Placing Animals in the Neolithic: Social Zooarchaeology of Prehistoric Farming Communities. London: UCL Press. ISBN978-one-84472-092-7.

External links [edit]

- Crop Wild Relative Inventory and Gap Analysis: reliable information source on where and what to conserve ex-situ, for ingather genepools of global importance

- Word of brute domestication with Jared Diamond

- The Initial Domestication of Cucurbita pepo in the Americas 10,000 Years Ago

- Cattle domestication diagram

- Major topic 'domestication': free full-text articles (more 100 plus reviews) in National Library of Medicine

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domestication

Posted by: bowleytroses.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Main Factor In Determining Domestication Of A Plant Or Animal Quizlet"

Post a Comment